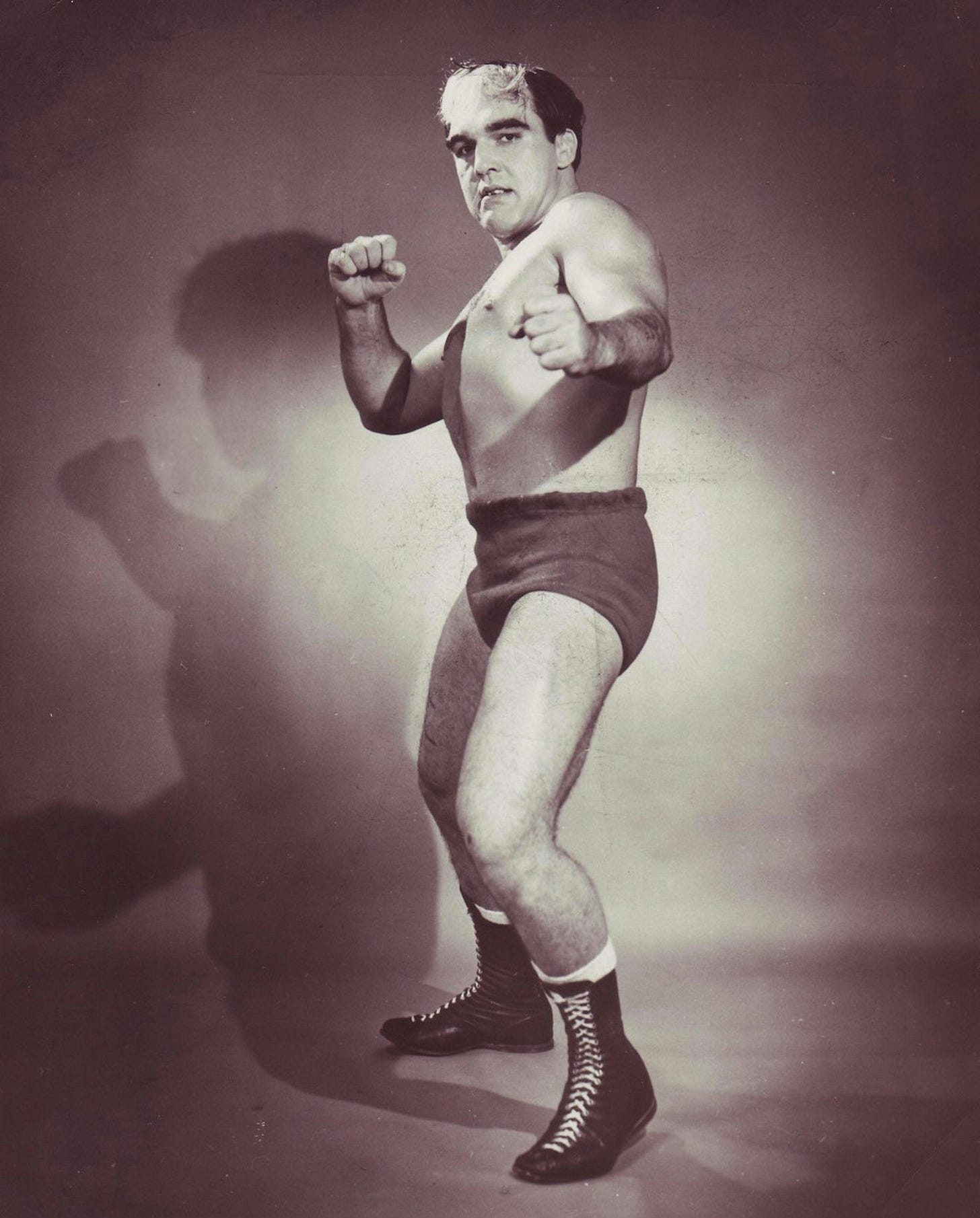

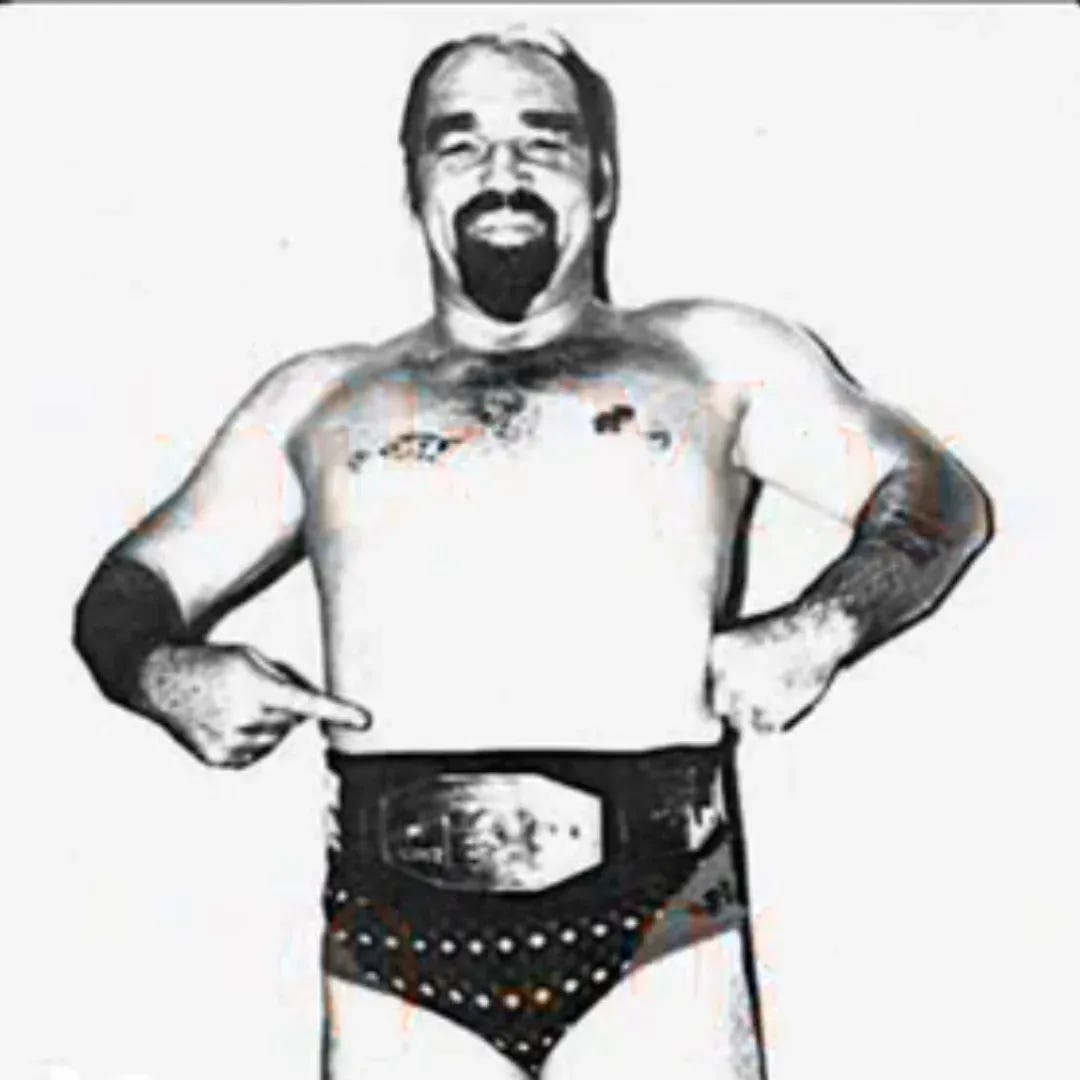

Sputnik Monroe

The wrestler who sold the hottest ticket in Memphis and then told the city where to sit.

He didn’t just change who won. He changed where people sat. On a Memphis Monday the building moved like weather: a white streak cutting through cigarette haze; a balcony packed to the beams; an aisle that felt like a dare; a man in a cape telling a city how it was going to spend its evening. Sputnik Monroe wasn’t a folk tale that got bigger in the retelling. He was a weekly habit that forced a civic one.

The easy version says he refused to wrestle until Black fans could sit on the floor. The truer version is more revealing, and harder to shrug off: the balcony was selling out, the floor wasn’t; he was the top draw; he leveraged that to make the room behave. There are better morality plays. There aren’t many better outcome charts.

“You could hear him from the street. And somehow the room bent toward him.”

The nickname came from an insult, and the insult came from a woman who ran out of words. Late 1957, Mobile TV, WKRG-5. Roscoe Brumbaugh had driven south from the Pacific Northwest, exhausted, and picked up a Black hitchhiker to split the miles. He asked the hitchhiker to drive while he slept off the road dust, then walked into the studio with his arm around him. A few rows in, an elderly white woman lost her composure. She spat slurs and, reaching for the week’s headline, grabbed the Cold War thing everyone was saying and few could explain:

“You’re a damn Sputnik.”

He didn’t even know the term yet. He knew a heat-getter when he heard one. Within weeks he was Sputnik Monroe. He leaned into it: the jet-black pompadour with the white streak; the one-liners you could sell merch with; the sly grin that said you could try to shut him up, but you’d have to buy a ticket.

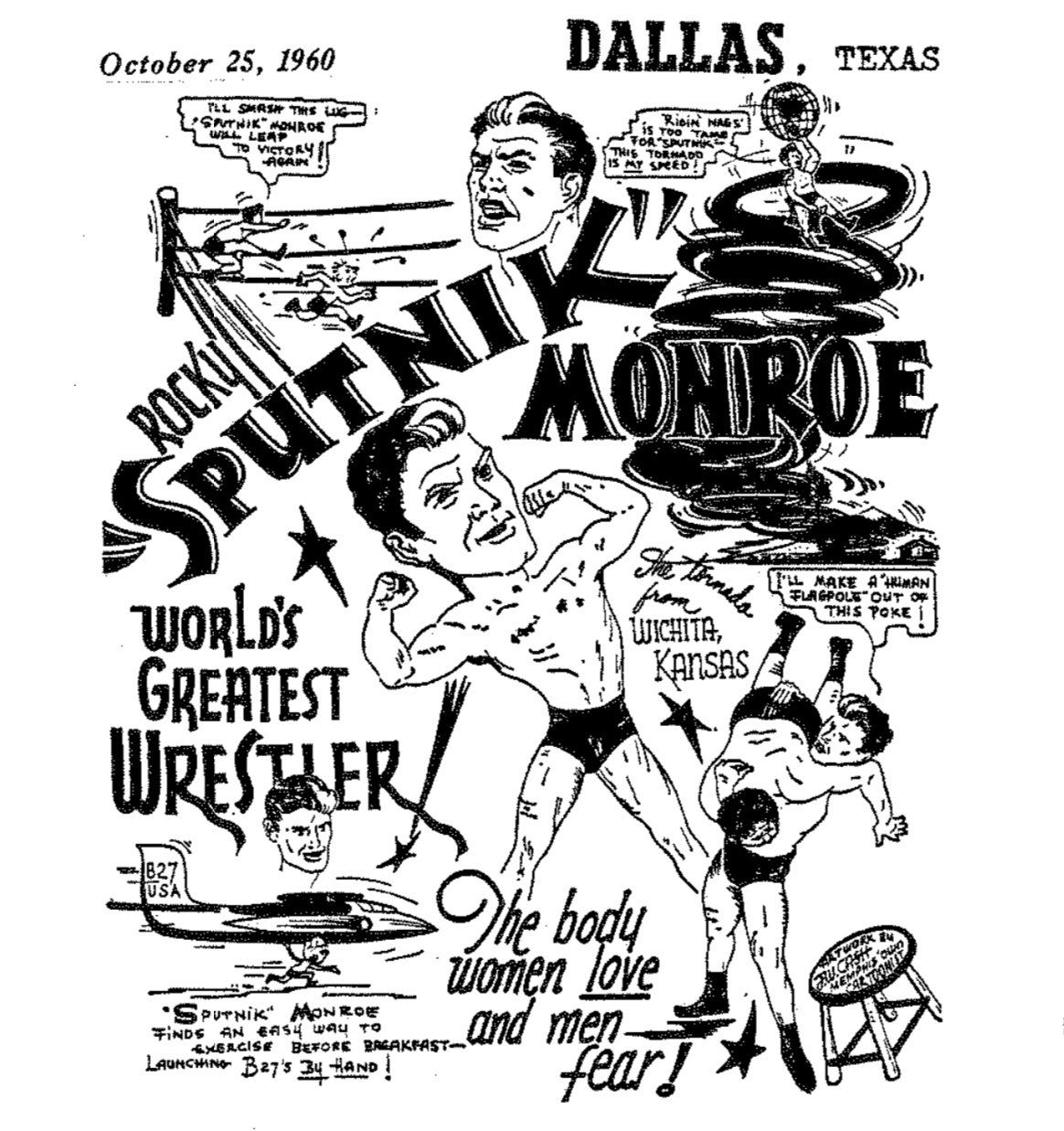

“Two-hundred-and-thirty-five pounds of twisted steel and sex appeal — the body women love and men fear.”

He styled himself the diamond ring and Cadillac man. Years later, Lance Russell dropped the line on TV and Monroe parried without blinking: “Lance, it’s turquoise ’n’ Toyotas now. Times are tough.” The mouth never slept.

He’d already been barnstorming long before the TV light hit him. Carnival rings. Athletic show challenges. Pretty Boy Roque and then Rock/Rocky Monroe across dusty cards where a talker survived better than a silent strongman. He studied the Red Berry trick, one fancy word, one audience wound. He learned you could sell more by talking than bleeding. He learned to treat a town like a mark and a mirror, not a backdrop.

Memphis was a perfect mark and a perfect mirror. He hit Beale Street like it owed him money. He drank where he liked, handed out tickets in cafés and clubs, told stories at the bar. The charge sheet called it mopery and attempted gawk. The city called it a nuisance. He called it advertising. Each arrest made the next Monday louder. It wasn’t performative charity. It was a man stepping where he intended to step, and then daring the room to stop him.

In 1960 he walked into Memphis city court with Russell B. Sugarmon Jr., a Black attorney, in 1960 Memphis, that stage picture landed as loud as any promo. He wasn’t chasing a Supreme Court test; he was making a picture: a white TV star in a suit, represented by a Black lawyer, glancing at a judge who kept a lid on the room. The fine was twenty-five dollars ($25). The headline was worth more.

“Wrestling desegregated Memphis before the city fathers did. And it was a heel that made it stick.” — Russell B. Sugarmon Jr.

“I’m not a do-gooder. I’m a doer.” — Monroe, years later, still half in character and half in confession

Memphis didn’t flip overnight. A habit began. Ellis Auditorium had a “crow’s nest” balcony where Black fans were corralled. The floor, the “good seats”, had space. Week after week, the balcony bulged; the floor did not. Monroe’s pay rode the house; Nick Gulas and Roy Welch’s did too. Same incentive, different microphone. He pushed with threats. He pushed with envelopes to ticket-takers, overselling the balcony until the safest fix was to wave the overflow onto the floor and let the room be a room. He pushed by selling out the main and letting the office say, hand on heart, that the heel forced their hand.

“Heel’s pay rode the house; the promoters’ did too. Same incentive, different microphone.”

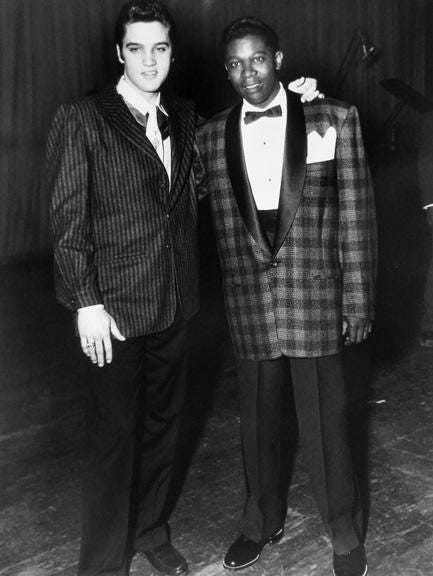

There was context beyond the ring. WDIA’s Goodwill Revue had already put Black stars and white faces in the same room at Ellis Auditorium in the mid-’50s, 7 December 1956, Elvis backstage with B.B. King while the Moonglows worked the bill. Those nights were the exception that proved a point: Ellis could mix when the draw demanded it. Wrestling turned “exception” into routine. Memphis had already tested mixed rooms when the music demanded it; wrestling made the mix a weekly habit, not a special night.

Memphis context: how Ellis Auditorium sat inside the city’s own timeline

1955 — Memphis Zoo “white days” fade under pressure

1956–57 — WDIA Goodwill Revue shows Ellis Auditorium can mix rooms for music one night a year

1957 — Sputnik hits Ellis Auditorium as a top heel and starts pushing over balcony sellouts

1959 — Russwood Park overflow proves mixed crowds can be handled at scale

1960–62 — Brooks Gallery and public libraries desegregated under legal and civic pressure

1963 — Watson v. City of Memphis: the Supreme Court ends the foot-dragging on parks and pools

Ellis Auditorium wasn’t first in principle, but it was first as a civic habit: a mixed entertainment crowd, weekly, without a court order. Wrestling as muscle memory where policy was still theory.

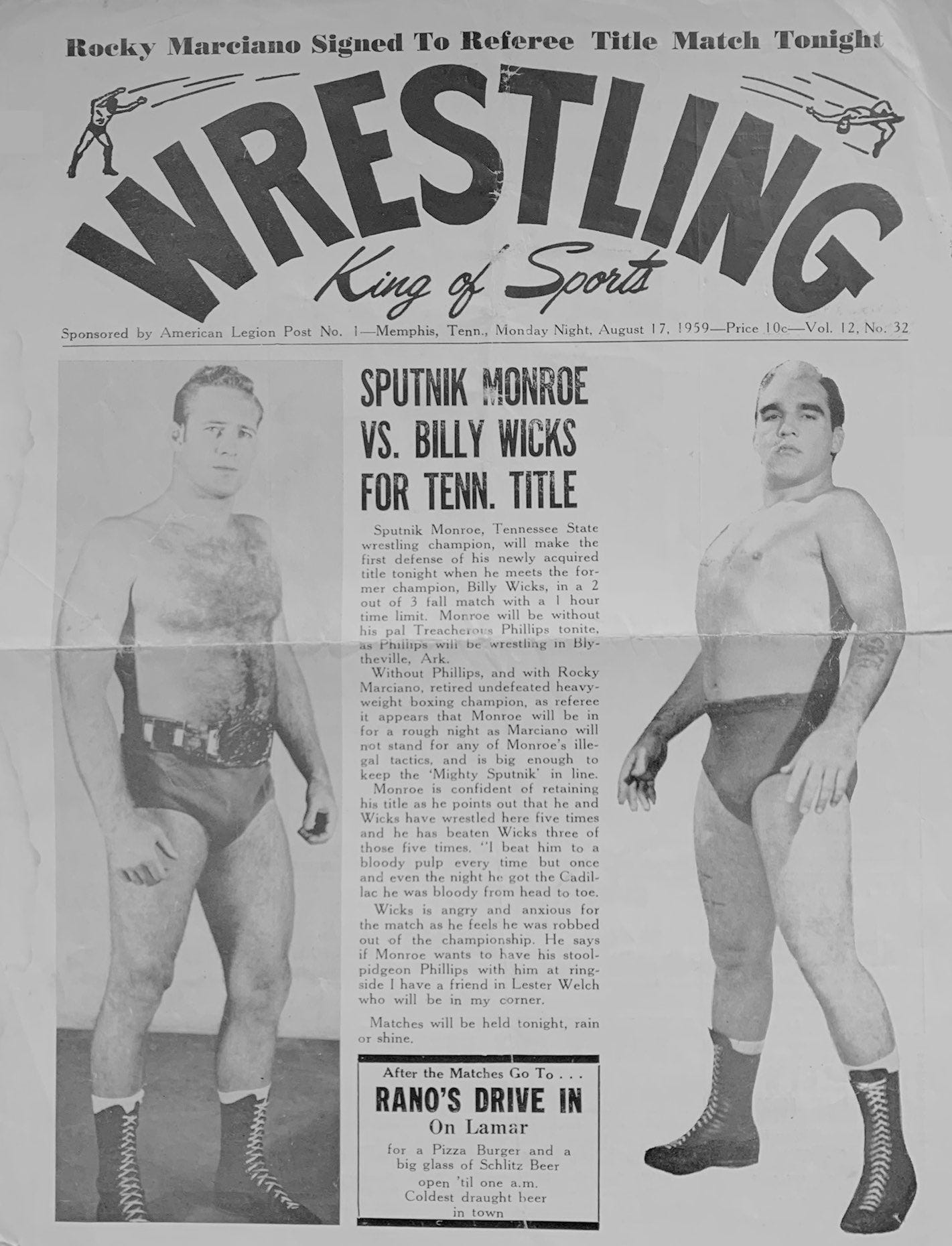

Monday 17 August 1959 is the poster that still hums. Sputnik Monroe vs Billy Wicks for the Tennessee title at Russwood Park, with Rocky Marciano in a striped shirt and a Cadillac in the copy. Russwood sat around fourteen thousand for a ballgame. That night the fences did not hold. People poured over outfield rails and blinked into floodlights. You can still find the programme, ink that promises morals while admitting what it really sells:

Two out of three falls, one hour, rain or shine.

“Marciano won’t stand for Sputnik’s illegal tactics.”

“I’ve beaten Wicks three of five; beat him to a bloody pulp.” — the heel, suited and smirking.

After the bell, Rano’s Drive-In on Lamar. Monday as ritual.

“The building was shaking. Sputnik was the guy that sold it.” — Billy Wicks

Marciano stopped the bout and levelled Monroe with a right hand. Nobody drove a new car home. The number is argued still, in the high teens, maybe twenty if memory has had a pint, but the point isn’t the final count. For decades, the city used that night as a yardstick and smiled. Ask five old-timers and you’ll hear seven totals; more telling, you’ll hear the same noise: fences giving up, kids on shoulders, the punch retold with the emphasis moving around like the spotlight.

A few weeks later, at the Mid-South Fair rodeo, he turned up bruised badly enough to set tongues off. One report blamed a Brahma bull. Eyewitnesses said a cowboy named Ray “Kid” Marley landed a right after Monroe went heavy on the lip in the chutes. Either way, he wore the stitches to the next town and the next poster. Buddy Fuller clocked the moment and tried to book the grudge. With a good heel, even the off-night becomes a gate.

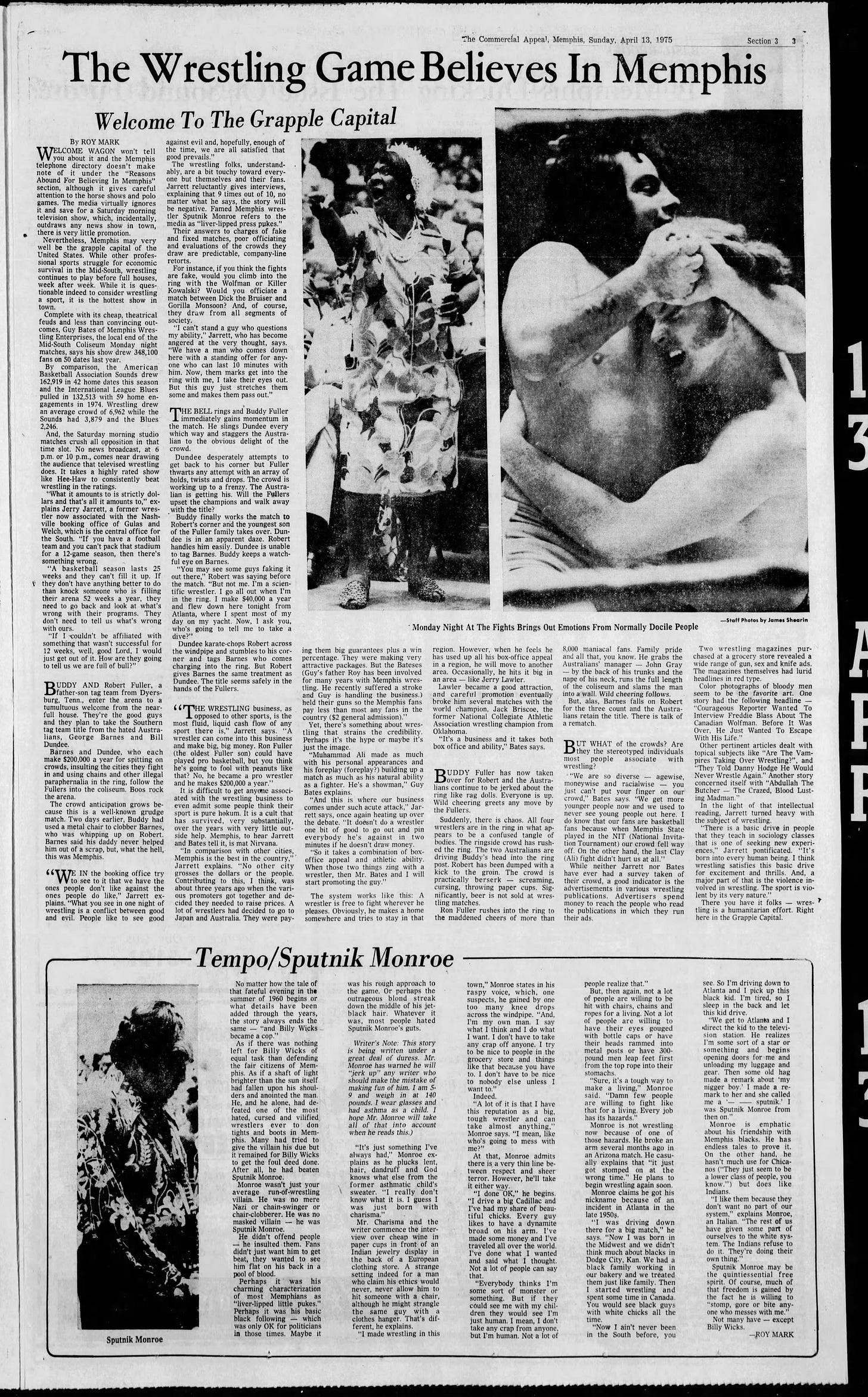

Memphis wrote him into itself while the tills still rang. On 13 April 1975 the Commercial Appeal gave wrestling a full Sunday page, “The Wrestling Game Believes in Memphis,” and boxed an on-page “Tempo/Sputnik Monroe” column. Not sepia. Present tense. The city calling itself the Grapple Capital and placing his name inside that sentence.

He travelled better than cynics allow. The home poster made him a star; the away fixtures prove the act wasn’t a provincial novelty.

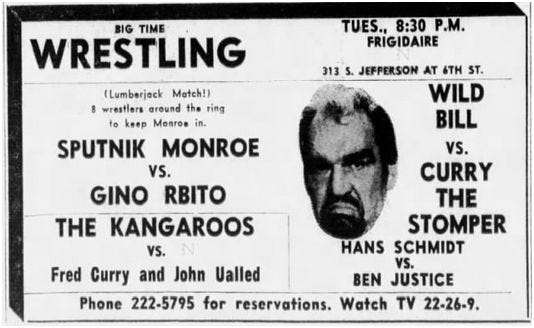

Dayton, Feb–Mar 1970, Frigidaire Union Hall (Local 801, 313 S. Jefferson). Four straight Tuesdays topped by Sputnik vs Fred Curry or Gino Brito. The ad copy in bold caps: No stopping on account of blood. Texas Death Match. Prices set out like an affidavit: Ringside $3.50, General $2.50, Kids half-price. Low rafters, hot room, cigarettes and whistles from the back row. You don’t run four consecutive union-hall tops unless the mouth is bringing them back to see if someone finally shuts him up.

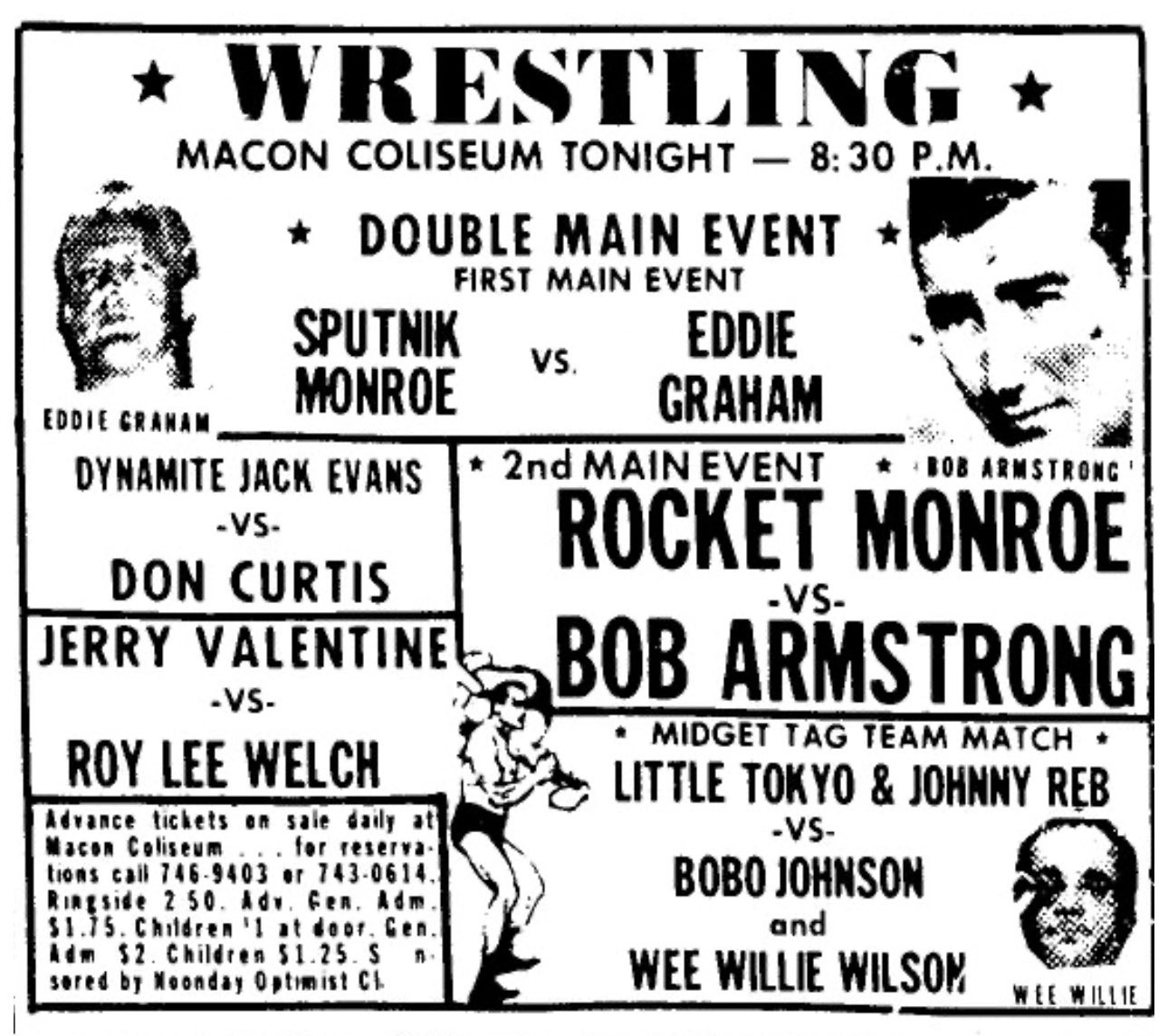

Macon Coliseum, 27 December 1972. Double main: Sputnik vs Eddie Graham; Rocket Monroe vs Bob Armstrong. Two Monroes tells you the surname and the streak travelled. Cold air off the ice, PA hum, kids waving rolled-up programmes like batons. Eddie didn’t waste card space; the office used acts that did business.

Atlanta Municipal Auditorium (Georgia Championship Wrestling). A busy twelve-month run made the surname feel local: 15 December 1972; 17 June 1973; 5 April 1974. Frequency matters as much as any single finish. If you’re a novelty, you don’t pulse back across three calendars.

Georgia snapshots (proof he wasn’t a Memphis-only quirk):

– Atlanta Municipal Auditorium: 15 Dec 1972, 17 Jun 1973, 5 Apr 1974 (Georgia Championship Wrestling TV + house)

– Macon Coliseum: 27 Dec 1972 (vs Eddie Graham; Rocket vs Bob Armstrong)

– Columbus cards through 1973 (Sputnik slotted in semi-mains)

– Augusta Civic Center, occasional pairings into early 1974

That’s a solid year’s worth of Georgia bookings across two hubs and satellite towns, the act travelled and got reused.

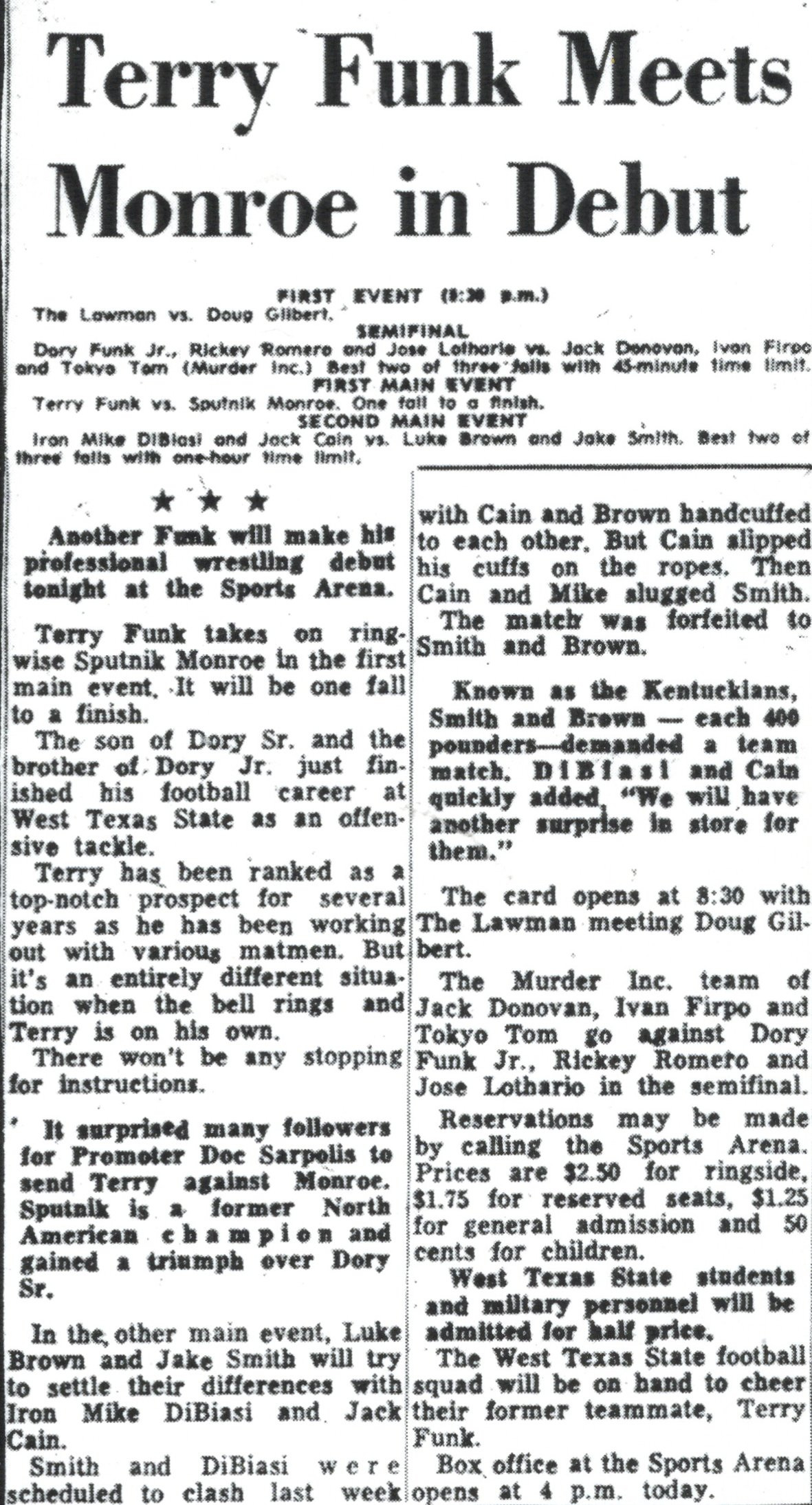

Amarillo, 9 December 1965. Terry Funk’s debut. Dory Funk Sr. and Doc Sarpolis didn’t feed a future NWA Worlds champion to a soft touch. They gave him a veteran with heat and timing. Prices spelled out: $2.50 ringside, $1.75 reserved, $1.25 general, 50¢ children. Dry dust in the car park and a bell that bounced off tin. Want to see a territory’s priorities? Look at the debut dance. They trusted Monroe to teach a lesson, not just take a fall.

Dallas, 25 October 1950. A cartoon broadside with a grinning heel in a tornado, speech bubbles everywhere and, across the bottom in bigger type than the opponents, the catchphrase. The act sold in Memphis. It sold in Texas. It sold wherever the aeroplane took him. If you’re a novelty, you don’t get the poster’s bottom strip to yourself.

He wasn’t just a Memphis quirk. In Houston he paired with Dory Dixon and the City Auditorium did what good rooms do when you book what people want: it filled. Dixon was a Black star who’d made his name in Mexico; pairing him opposite or alongside Sputnik put an inter-racial match on a weekly loop where the office cared about one thing, does it sell? It did. Paul Boesch could lecture a worker and still book him on top if the receipts behaved, and they did here. The taboo looked silly next to the till. In a business that measures morality by the queue at the box office, that’s the clearest proof there is that the act travelled and the integration angle wasn’t a one-city storyline.

Dallas and Houston proved the taboo would blink if the turnstiles asked it to; Atlanta kept the surname warm on TV and the loop.

Atlanta. Municipal Auditorium dates alongside Georgia Championship Wrestling TV made the streak a familiar TV face and a house-show main when you needed one.

Selected title résumé (the bits that actually drove houses and angles)

– NWA World Junior Heavyweight Championship (1, 1970) — brief run in the Hodge cycle; Monroe asked Leroy McGuirk to switch it back when the punishment started to cost next week’s miles.

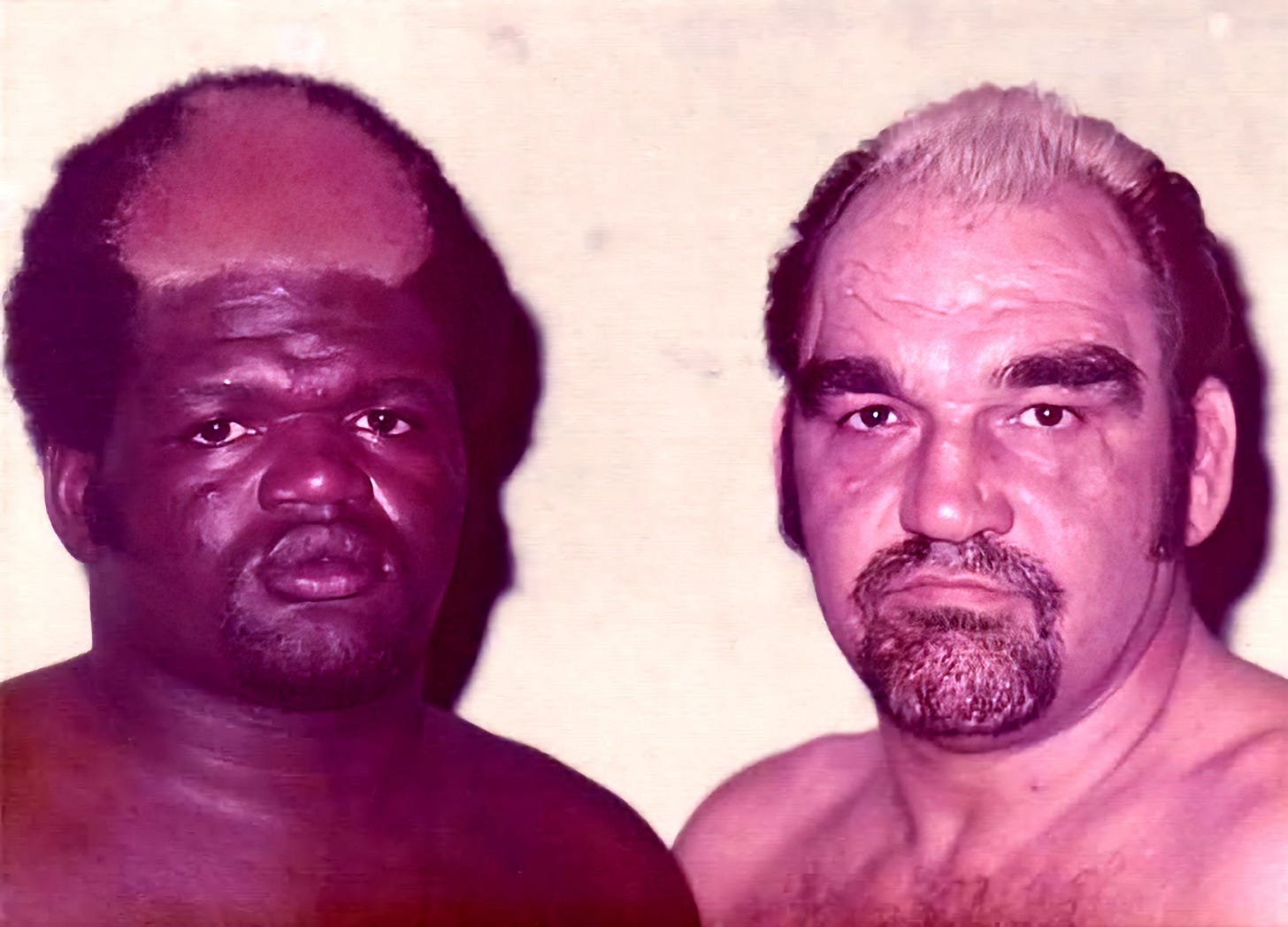

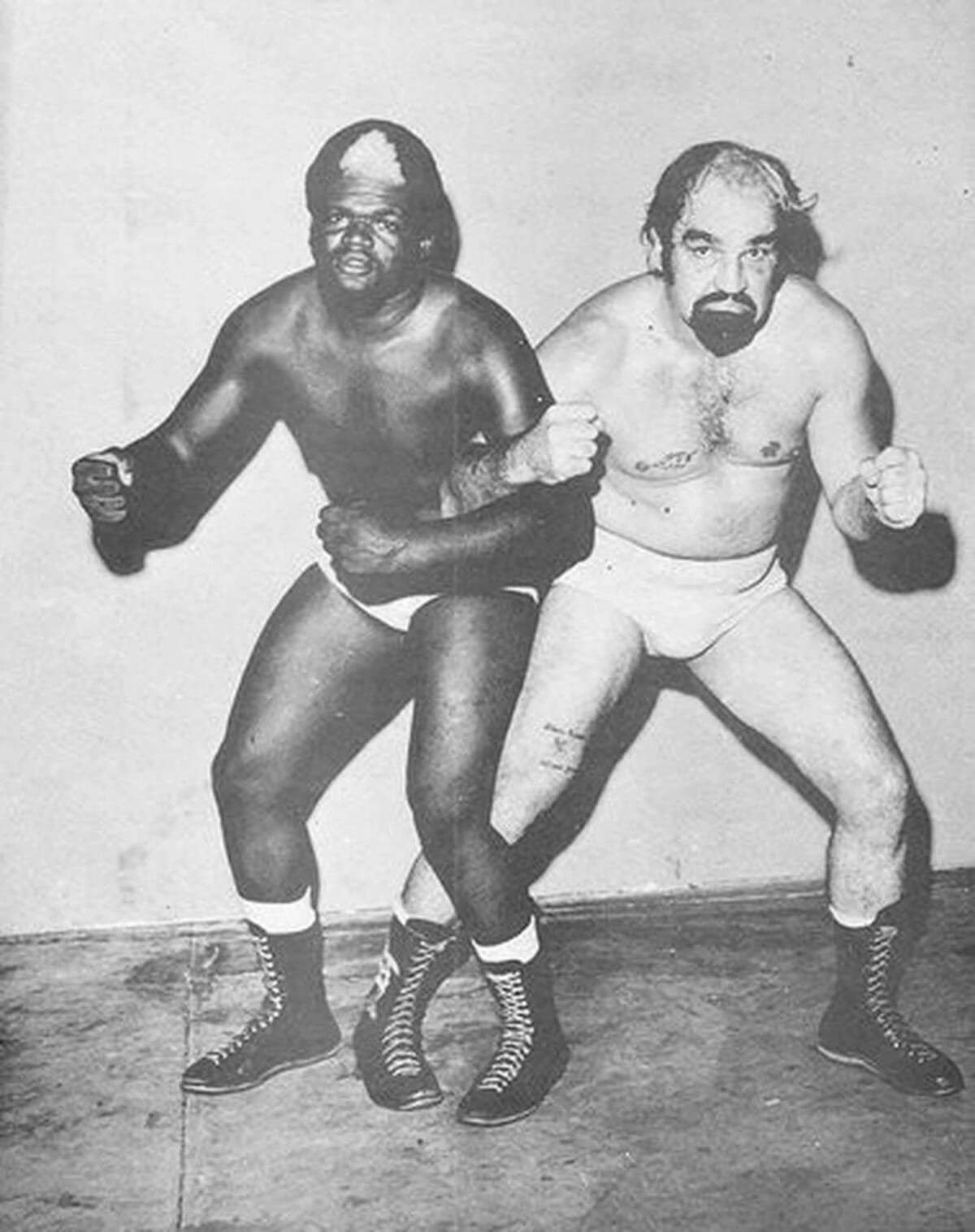

– AWA Southern Tag Team Championship (Memphis) — multiple runs with Norvell Austin during the salt-and-pepper TV push that converted heat into weekend houses (documented in Memphis listings).

– NWA Florida Tag Team Championship (CWF) — with Norvell Austin, proof the act travelled and drew beyond Tennessee (documented in Florida listings).

– NWA Gulf Coast Tag Team Championships — with Rocket Monroe (Bill Fletcher/Maury High) and later with Flash Monroe (Gene Dundee); the “family” let the surname headline and semi on the same loop.

– Spread of territorial junior/heavy belts across Tennessee/Alabama/Gulf Coast — short reigns used as angle engines, not mantelpieces.

The point isn’t counting plates. The point is how he used them: quick flips to spark the next Monday; tag straps that normalised Black/white teams drawing money as heels and set the lane for Rossi & Bearcat to thrive as babyfaces.

Then came the bit that belongs on television and in a museum. Early ’70s Southern TV, a Black partner with a matching white streak, two heels who loved paint and microphones. Norvell Austin stood next to him and they hit the cadence like a gospel call-and-response:

“Black is beautiful.”

“White is beautiful.”

“Black and white together is beautiful.”

On paper it reads cute. In a hall full of history it drops heavy. The chant turned tension into product. They took letters and threats; they kept the cadence anyway. A year on, Len Rossi & Bearcat Brown were babyface beloved on the same loop. The first push kicks a door. The next lads bring in the furniture.

He was the kind of southern main-event heel a booker trusts: strong, rough, funny, cruel on cue, twenty minutes you could set your watch by and a finish even the kids upstairs could follow. In 1970 he held the World Junior Heavyweight belt long enough to tell Leroy McGuirk to take it off him since Danny Hodge was chewing his ribs for supper. That isn’t weakness. That’s a pro saving himself for tomorrow’s town. Hodge could make a man’s hand vanish in his grip; plenty bragged later. Sputnik turned it into a practical note: switch this back; more dates on the board.

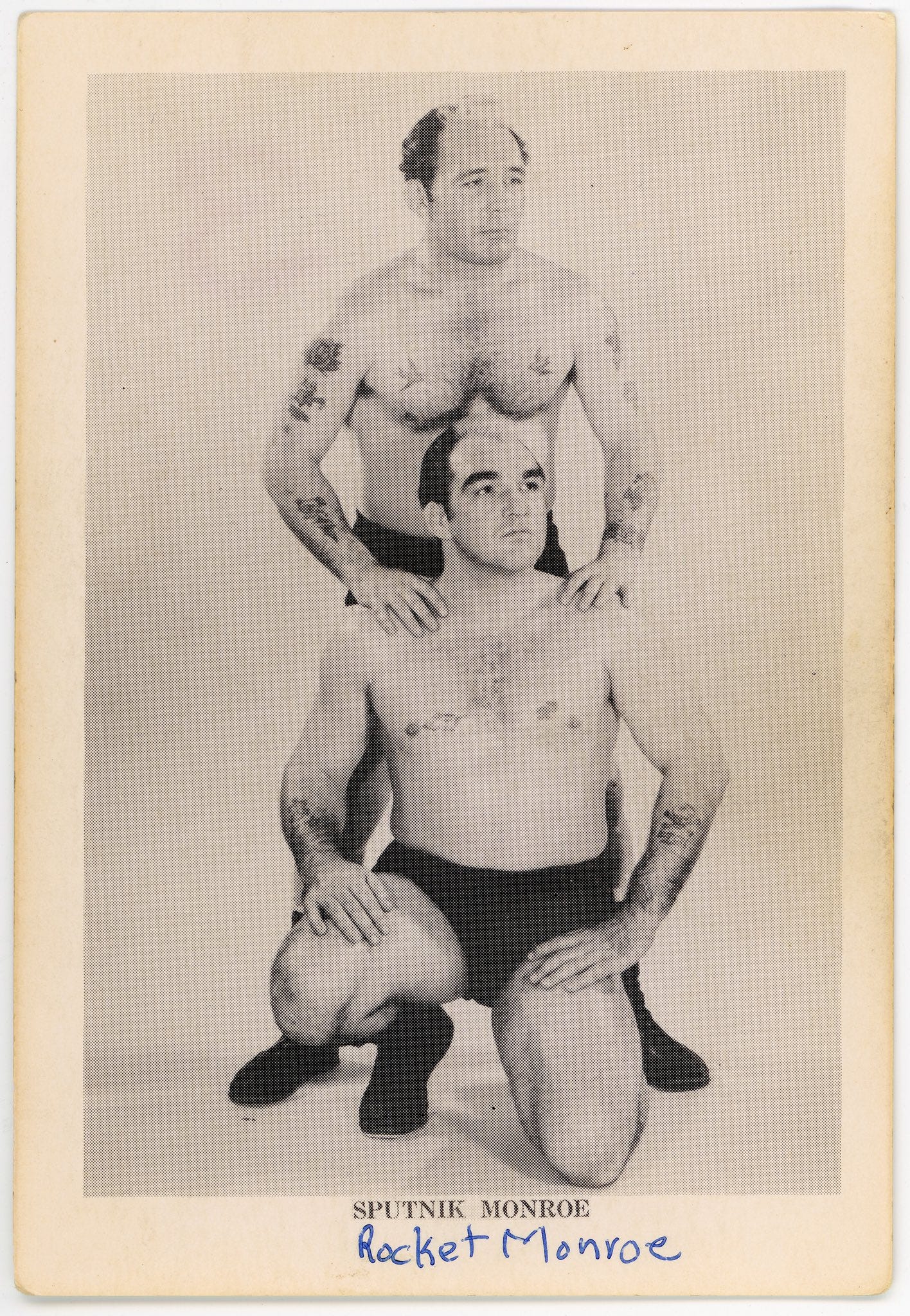

The surname became a travelling franchise. Here’s the Monroe chronology so readers stop guessing:

– 1959 (Gulf Coast): brief one-week cameo by Jody Hamilton as Ricky “Rocket” Monroe — prototype asterisk.

– Early 1960s: Bill Fletcher as the first proper Rocket; white streak dyed to match; pairing framed as brothers; Gary Brumbaugh working as Jet Monroe in the corner.

– 1963–1969: Maury High takes the Rocket identity and becomes the best-known version, teaming with Sputnik across Gulf Coast, Mid-South and Georgia shots.

– 1969: Gene Dundee (Gino Sannizzaro) is repackaged as Flash Monroe; three-Monroe combinations headline and semi on the same loops.

– 1970s: with Norvell runs, the “family” overlaps with salt-and-pepper heat; later, Bubba Monroe appears into the ’80s, keeping the surname live.

Memphis lived inside a small triangle: Ellis at Poplar and Front; Beale two turns away; Rano’s out on Lamar. Wrestling in that wedge wasn’t a diversion. It was a weekly appointment the city talked about at lunch and settled with after work. Elsewhere, the public spaces inched: zoo days, gallery hours, library desks, court orders. Wrestling moved the blunt way: open the floor and sell it. People follow money and rhythm better than memos. Ellis adjusted because a heel made it costly not to.

A few local voices sharpen the picture. Marilyn Lowery remembered him around 1970, ferrying Jackson Lemon Cookies to neighbourhood kids near a corner shop on Josephine and Midland and treating them like they were part of his show. Bob Massie heard him on TV tell Lance Russell the diamond ring and Cadillac man had switched to “turquoise ’n’ Toyotas”; the gag landed because it was close to the bone. The catchphrase he minted became shared property in the territories, Dusty Rhodes, Superstar Graham, Austin Idol, Gino Hernandez, Michael Hayes, Eddie Mansfield, Don Greene, Paul Orndorff, all doing riffs on the “twisted steel and sex appeal” cadence that Sputnik banked first.

You can counter-programme this story with quibbles. Lance Russell often said Gulas and Welch wanted the mixed floor as much as anyone; letting the heel take the heat was useful theatre. That strengthens the case. Wrestling is theatre that moves bodies. If the office used a heel to make a civic change look like the heel’s idea, that’s pro wrestling doing what it’s built to do. And the change held. That’s the measure.

When the mask of TV heat drops you get the NPR voice: battered but bright, telling the hat story, walking into a shop with a friend, refusing to let him remove his Homburg, “we may have a fight but we’re not taking our hats off.” You get the Houston shuttle years, the charm that didn’t age out. When someone repeated the myth that Ed “Strangler” Lewis made seventeen million dollars, he did the arithmetic aloud: “Let’s see, multiply $25 by six nights a week by 52 by 25 years.” He’d still ring a reporter at midnight like it was the five-minute call in a TV studio, voice gravelly and ready.

The Wrestling Observer Hall of Fame asks for three things: drawing power, ring work, historical impact.

Drawing power is Russwood plus the away receipts. The Commercial Appeal crowned Memphis the Grapple Capital in 1975 and boxed a Sputnik column on the same page; that’s a town validating the man who filled its Mondays. The road run is legible on paper: Dayton’s four Tuesdays with blood and Texas Death in the copy; Macon’s double main with Eddie Graham and Bob Armstrong; Atlanta Auditorium dates in Dec ’72/Jun ’73/Apr ’74; Amarillo’s Terry Funk debut; Dallas cartoon broadsides; steady Houston usage with Dory Dixon. Add the smaller clippings, union-hall prices, the “no stopping on account of blood” line, the cartoon tornado, and you have texture, not a thesis floating on vibes. Even modern Hall primers file him under impact-first, draw proven enough.

Ring work is the southern main-event heel brief. He was trusted to launch Terry Funk, to carry Billy Wicks to a roof-lifter, to take Danny Hodge until good sense intervened. Not St. Louis sleek; dependable, mean on demand, funny when mouths needed opening, safe enough that offices kept pencilling him on top. The job is to get them in, point them at the babyface, and make sure they come back next week to see if justice finally lands. He did the job.

Historical impact is the crux. A white TV star who openly courted a Black audience; who stood next to Russell Sugarmon in city court because the picture mattered; who helped turn mixed seating at Ellis from controversy into habit; who put “Black and white together is beautiful” on Southern TV and then let the territory get on with it. Fold in the Houston bills with Dory Dixon and you get a pattern, not a one-off. Fold in the 1975 Commercial Appeal spread while he was still active and you get confirmation in real time, not romantic hindsight.

And this isn’t just theory, Sputnik Monroe is already picking up votes in the Observer electorate. Across the last three ballot cycles, a mix of historians, podcasters, analysts and long-time voters have gone public with their support.

2024: Al Getz; Alan Counihan (Alan4L); Allan Cheapshot; Anonymous Voter #4; Crimson Mask from FL; Dan Cerquitella; Dan Farren; Dave Musgrave; David Bixenspan; David Wolf; Dylan Hales; Edward Loredo; Fred Morlan; George Atsaves; Jamie Sessions; Jeremy Finestone; Joel Abraham; Jonathan Hood; Jonathan Snowden; Josiah MacDonald; Kris Zellner; Mark Coale; Mike Gilbert; Mo Chatra; Paul Fontaine; Pete Shoe; Rich Kraetsch; Tony Richards

2023: Al Getz; Alan Counihan (Alan4L); Allan Cheapshot; Crimson Mask from FL; Dan Cerquitella; Dan Farren; David Bixenspan; Edward Loredo; Fred Morlan; George Atsaves; Griffin Peltier; Jamie Sessions; Joel Abraham; Kris Zellner; Mark Coale; Roy Lucier

2022: Al Getz; Alan Counihan (Alan4L); Allan Blackstock; Brian R. Solomon; Dan Farren; Dave Dynasty; Dave Musgrave; David Bixenspan; Kris Zellner; Mark Coale; Matt Ryan; Mister Ooh-La-La; Mo Chatra; Rich Kraetsch; Thomas Simpson; Will Cooling; Yusuke Okamoto

That spread of names shows his support runs across statisticians, historians, podcasters and territory specialists. You can clock it against other respected “borderline” names and it holds up. The same public-ballot circles that rally to JYD or the Von Erichs keep showing for Sputnik, which tells you his case isn’t niche taste, it sits in the same lane as candidates voters already take seriously.

For readers who want the receipts in one place, here’s the short line:

– Late 1957, Mobile (WKRG-5). Walks into the studio with a Black driver, kisses him on the cheek to wind up a heckler, inherits “Sputnik” from someone who ran out of words.

– 1957–60, Beale Street. Repeated arrests; small fines; Russell B. Sugarmon Jr. as counsel; the image as both moral and marketing choice.

– 7 Dec 1956, Ellis Auditorium. WDIA Goodwill Revue with B.B. King, the Moonglows, and Elvis seen backstage, proof Ellis could mix a room when the bill demanded it.

– 17 Aug 1959, Russwood Park. Wicks vs Monroe, Marciano referees; fences give; programme promises; Monday becomes civic theatre.

– Sept 1959, Mid-South Fair. “Bull” vs Kid Marley punch-up; either way, bruises you can sell next week.

– 25 Oct 1960, Dallas. Cartoon broadside; catchphrase printed larger than the opponents.

– 9 Dec 1965, Amarillo. Terry Funk’s debut vs Monroe; prices itemised; office trust.

– Feb–Mar 1970, Dayton. Four Tuesdays at Frigidaire Union Hall; No stopping on account of blood; Texas Death; prices in ink.

– 27 Dec 1972, Macon Coliseum. Double main: Sputnik vs Eddie Graham; Rocket vs Bob Armstrong.

– 15 Dec 1972 / 17 Jun 1973 / 5 Apr 1974, Atlanta Municipal Auditorium. Regular Georgia Championship Wrestling use keeps the surname warm on TV and house loops.

– Early ’70s TV. Norvell Austin with the matching streak; “Black/White… together” cadence that lands heavy in halls.

– 13 Apr 1975, Commercial Appeal. Full Sunday page: “The Wrestling Game Believes in Memphis.” Boxed “Tempo/Sputnik Monroe.”

A few honest edges help the vote:

– He was a heat merchant first. The civil-rights outcomes ran through the tools of a heel: provocation, leverage, repetition. Plenty of wrestling’s useful social changes arrive in the backwash of someone chasing a house.

– He stayed rough. Not a St. Louis clinic. A Memphis draw who could talk you in, cheat in plain sight, and leave with your Monday next week. For the Hall, that’s the southern main-event job description.

– He spun yarns like any carny worth salt. The bull that kicked him, the cowboy who clocked him, the number at Russwood, the shine got brighter with each retelling. The outcomes remain.

He didn’t heal the city. He did something stranger and more useful. He made it act like the poster said it should, for a couple of hours, every week, until the seating plan stopped being a fight.

“Black is beautiful… White is beautiful… Black and white together is beautiful.”

Tick the box.

How to read your Historical NA ballot in this case (one-screen explainer for voters)

If you vote in Historical North America, you’re weighing three equal prongs: drawing power, ring work, historical significance. Sixty percent on the regional ballot gets a candidate in. Integration outcomes sit squarely within “historical significance” under the Newsletter’s rubric, and Sputnik clears that prong decisively (mixed seating at Ellis turning from flashpoint to routine; Black/white teams normalised as weekly TV business) while showing solid evidence on the first (Russwood; Commercial Appeal’s 1975 spread during his active run; receipts in Dayton/Macon/Amarillo/Dallas/Houston/Atlanta). On work, he’s the archetype of the southern main-event heel: timing, heat, safety, trust (launching Terry Funk; carrying Wicks; taking Hodge until prudence took over).

This isn’t a niche push. Public ballots from 2022–24 sit in the same circles that back JYD, the Von Erichs and other “borderline but respected” historical names, same evaluative lane.

If your mental checklist needs one last nudge:

– Did he draw? Enough to become front-page culture in Memphis and headline credibly on the road.

– Did he do the role? Offices trusted him to start Funk, heat Wicks, and keep loops healthy.

– Did he matter beyond finishes? A heel who made mixed seating a weekly habit, then turned “salt and pepper” from controversy into business.

That’s a Hall profile. Tick the box.